Orbán Viktor megérkezett Egyiptomba, ahol konferenciát tartanak a gázai háború lezárásáról.

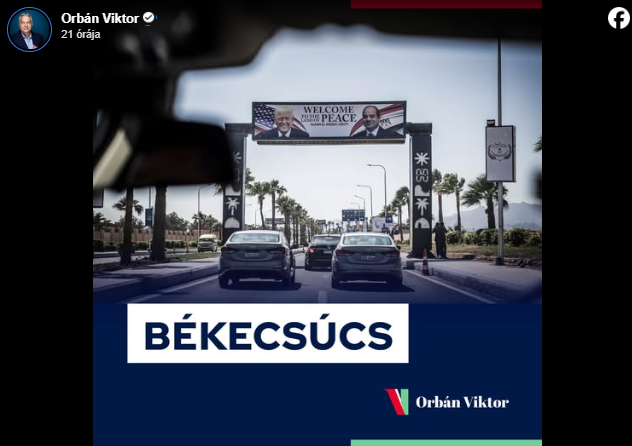

Hétfőn Sarm es-Sejkben tartanak békekonferenciát. A gázai háborút lezáró csúcson Orbán Viktor miniszterelnök is részt vesz, és Facebook-oldalán tett is közzé erről egy üzenetet:

Itt tekintheted meg Orbán Viktor miniszterelnök úr Facebook-posztjait!

Abdel-Fattáh esz-Szíszi egyiptomi államfő és Donald Trump amerikai elnök vezeti az egyiptomi Sarm es-Sejkben hétfőn tartandó békekonferenciát, amelyen hivatalosan is aláírják az izraeli háborút lezáró békeszerződést az izraeli és palesztin felek – jelentette be az egyiptomi elnöki hivatal, hozzátéve, hogy az eseményen több mint 20 ország vezetője, illetve az ENSZ-főtitkár is jelen lesz. A békecsúcson részt vesz Orbán Viktor is.

Donald Trump hétfő délelőtt Izraelbe érkezett rövid látogatásra, hogy beszédet mondjon az izraeli parlamentben. Beszéde előtt szűkkörű megbeszélésen vett részt Benjámin Netanjahu miniszterelnök irodájában, melyen részt vett Steve Witkoff, az Egyesült Államok közel-keleti különmegbízottja és Jared Kushner, az elnök veje és tanácsadója.

A tanácskozáson telefonbeszélgetést folytattak Abdel Fattáh esz-Sziszi egyiptomi elnökkel, aki meghívta az izraeli kormányfőt a délutánra, a Donald Trump amerikai elnök vezette békekonferenciára, amelyen hivatalosan is aláírják a gázai háborút lezáró szerződést.

Netanjahu a telefonbeszélgetésben beleegyezett részvételébe az izraeli 13-as kereskedelmi televízió korábbi értesülése szerint. A konferencia célja, hogy véget vessen a Gázai övezetben dúló háborúnak, megerősítse a Közel-Kelet stabilizálására és békéjére tett erőfeszítéseket, és új fejezetet nyisson a térség biztonsági helyzetében.

António Guterres ENSZ-főtitkár jelezte részvételét, a Downing Street tudatta, hogy Sarm es-Sejkbe utazik Keir Starmer brit miniszterelnök is, aki egyúttal „történelmi fordulópontnak” nevezte a hétfői eseményt.

Ott lesz II. Abdalláh jordániai király, Friedrich Merz német kancellár, Emmanuel Macron francia államfő, valamint Pedro Sánchez spanyol és Giorgia Meloni olasz kormányfő, és Mahmúd Abbász a Palesztin Nemzeti Hatóság elnöke is. Az Európai Uniót Antónia Costa, a tagállami vezetőket tömörítő Európai Tanács elnöke fogja képviselni.